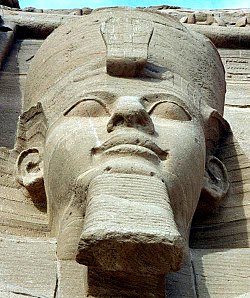

Ramses II

Ramses II au Rameses Mkuu au Sese (1303 hivi - Julai au Agosti 1213 KK)[1] alikuwa Farao wa Misri miaka 1279–1213 KK, wa tatu katika Nasaba ya 19 ya Misri ya Kale.

Mara nyingi anasifiwa kama Farao bora. Waandamizi wake na Wamisri wa baadaye walimuita "Mzee Mkuu".

Ramses II aliongoza majeshi yake mara kadhaa hadi Asia, ili kusisitiza himaya ya Misri juu ya Kanaani, lakini pia kusini hadi Nubia.

Tena alishughulikia sana ujenzi wa miji n.k. Pia kwa sababu hiyo, wengi wanaona ndiye Farao aliyepambana na Musa kadiri ya Biblia.

Maisha[hariri | hariri chanzo]

Ramses II alikuwa mfalme wa pili wa Nasaba ya 19 ya familia ya kifalme na alikuja kuwa miongoni mwa Mafarao wenye nguvu kuwahi kuwepo Misri.

Ramses II alipewa kiti cha Ufalme mapema kwenye umri wa miaka 20 akaongoza kati ya mwaka 1279 KK hadi alipofariki miaka 67 baadae (1213 KK) kwa maradhi ya mishipa, na ini. Hivyo aliongoza Misri kwa miaka 67 akiwa wa pili kuongoza kwa kipindi kirefu zaidi katika historia ya mafarao.

Mbali na Vita Ramses II anakumbukwa mno katika juhudi za utunzaji wa Historia ya Misri katika mahekalu ya Ramesseum pamoja na Abu Simbel. Kwa kumbukumbu nyingi muhimu zilizomo katika mahekalu haya kwa sanamu, zana za kale, michoro na maandishi zinamfanya Ramses kuwa mmoja wa mafarao muhimu wa Misri ya kale.

Jeshi la Ramses lilisaidia kulinda mipaka ya Misri kutoka kwa wavamizi na majambazi katika Mediterania na Libya pia kutoka Wahiti na Wanubia.

Pia alifanya kampeni za kurudisha ardhi iliyokuwa imeporwa na wavamizi kwa kusaini mikataba ya amani kabla ya kutumia nguvu kuwapiga.

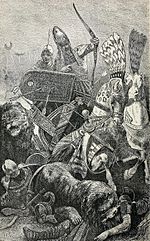

Katika historia Ramses alishindwa vita mara moja tu! vita inayokumbukwa sana ni ile iliyofanyikia Kadesh (Syria ya leo) mwaka 1274 KK dhidi ya Wahiti. Vilikuwa vita vikubwa vilivyotumia zana za kisasa zaidi wakati huo katika historia ya vita vya kale. Ramses alifanya makosa kwa kugawa vibaya vikosi vyake, kitu kilichofanya kimojawapo kufyekwa chote! Hatimaye mpinzani akajitangazia ushindi na Ramses ikampasa arudi nyuma sababu ya kujiandaa kubaya na matatizo ya vifaa.

Vitabu kadhaa vya dini vimekuwa vikizungumzia kifo chake katika hali ya kushangaza, vikidai kuwa Ramses alifia kwenye maji wakati akiwafukuza Waisraeli. Wamisri wa kale wakipinga kabisa madai hayo na kudai Sese alifariki akiwa na miaka zaidi ya 87 kutokana na maradhi ya kibinadamu. Moja ya ushahidi ni wa Mwili/Mumia wa Sese ambao unaonekana wazi kuwa mtu huyo alifariki akiwa mzee kabisa!

Wengine wanaenda mbali zaidi kuwa Ramses mwili wake huwa hautaki kuzikwa! Kumbe huyo mwanzo alizikwa kwenye kaburi KV7 katika Bonde la Wafalme, lakini kwa sababu ya uporaji wa vitu vya thamani alivyokuwa amevishwa, makuhani walihamisha mwili kutoka eneo hilo na kuupeleka ndani ya kaburi la malkia Inhapy.

Miaka mingi baadaye waliuhamishia tena mwili kwenye kaburi la kuhani mkuu Pinudjem II. Yote hii ni sababu ya kumbukumbu katika hiroglifi.

Kutokana na matetemeko yaliyoikumba Giza miaka kati ya miaka 1000 hadi 1500 BK vitu vingi vilipotea huku baadhi ya sanamu zikiharibiwa vibaya na matetemeko hayo, na baadhi ya makaburi, majumba, na makumbusho mengine kupotea kabisa! Mwili wa Ramses II nao ukipotea katika matetemeko hayo.

Mwanzoni mwa miaka ya 1800, mwili huu ulipatikana tena pembezoni kidogo mwa Bahari ya Shamu.

Ramses II, hakufa kwenye Gharika ya Musa kama watu wanavyodai, mwili wake hadi sasa unathibitisha kuwa alikufa akiwa mzee, zaidi ya miaka 80 kwa maradhi ya kawaida.

Pia si mwili wa Ramses II tu uliopo kwenye makumbusho ya Misri, ni miili mingi ya Mafarao tofauti na baadhi ya watu walioishi kwenye Misri ya kale.

Tanbihi[hariri | hariri chanzo]

- ↑ "Ramses". Webster's New World College Dictionary. Wiley Publishing. 2004. http://www.yourdictionary.com/Ramses.

Marejeo[hariri | hariri chanzo]

- Balout, L., Roubet, C. and Desroches-Noblecourt, C. (1985). La Momie de Ramsès II: Contribution Scientifique à l'Égyptologie.

- Bietak, Manfred (1995). Avaris: Capital of the Hyksos - Recent Excavations. London: British Museum Press. ISBN 0-7141-0968-1.

- von Beckerath, Jürgen (1997). Chronologie des Pharaonischen Ägypten. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern.

- Brand, Peter J. (2000). The Monuments of Seti I: Epigraphic, Historical and Art Historical Analysis. NV Leiden: Brill. ISBN 90-04-11770-9.

- Brier, Bob (1998). The Encyclopedia of Mummies. Checkmark Books.

- Clayton, Peter (1994). Chronology of the Pharaohs. Thames & Hudson.

- Dodson, Aidan; Dyan Hilton (2004). The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05128-3.

- Grajetzki, Wolfram (2005). Ancient Egyptian Queens– a hieroglyphic dictionary. London: Golden House Publications. ISBN 0-9547218-9-6.

- Grimal, Nicolas (1992). A History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-17472-9.

- Kitchen, Kenneth (1983). Pharaoh Triumphant: The Life and Times of Ramesses II, King of Egypt. London: Aris & Phillips. ISBN 0-85668-215-2.

- Kitchen, Kenneth Anderson (2003). On the Reliability of the Old Testament. Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 0-8028-4960-1.

- Kitchen, Kenneth Anderson (1996). Ramesside Inscriptions Translated and Annotated: Translations. Volume 2: Ramesses II; Royal Inscriptions. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 0-631-18427-9. Translations and (in the 1999 volume below) notes on all contemporary royal inscriptions naming the king.

- Kitchen, Kenneth Anderson (1999). Ramesside Inscriptions Translated and Annotated: Notes and Comments. Volume 2: Ramesses II; Royal Inscriptions. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

- Kuhrt, Amelie (1995). The Ancient Near East c.3000–330 BC. Vol. 1. London: Routledge.

- O'Connor, David; Eric Cline (1998). Amenhotep III: Perspectives on his reign. University of Michigan Press.

- Putnam, James (1990). An introduction to Egyptology.

- Rice, Michael (1999). Who's Who in Ancient Egypt. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-15448-0.

- Herbert Ricke; George R. Hughes; Edward F. Wente (1967). The Beit el-Wali Temple of Ramesses II.

- RPO Editors. "Percy Bysshe Shelley: Ozymandias". University of Toronto Department of English. University of Toronto Libraries, University of Toronto Press. Ilihifadhi kwenye nyaraka kutoka chanzo mnamo 2006-10-10. Iliwekwa mnamo 2006-09-18.

- Siliotti, Alberto (1994). Egypt: temples, people, gods.

- Skliar, Ania (2005). Grosse kulturen der welt-Ägypten.

- Stieglitz, Robert R. (1991). "The City of Amurru". Journal of Near Eastern Studies (The University of Chicago Press) 50.1.

- Tyldesley, Joyce (2000). Ramesses: Egypt's Greatest Pharaoh. London: Viking/Penguin Books.

- Westendorf, Wolfhart (1969). Das alte Ägypten (kwa Kijerumani).

- Can. Assoc. Radiol. J. 2004 Oct;55(4):211–7, PMID 15362343

- The Epigraphic Survey, Reliefs and Inscriptions at Karnak III: The Bubastite Portal, Oriental Institute Publications, vol. 74 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1954

- Drews 1995, p. 54: "Already in the 1840s Egyptologists had debated the identity of the "northerners, coming from all lands," who assisted the Libyan King Meryre in his attack upon Merneptah. Some scholars believed that Meryre's auxiliaries were merely his neighbors on the Libyan coast, while others identified them as Indo-Europeans from north of the Caucasus. It was one of Maspero's most illustrious predecessors, Emmanuel de Rougé, who proposed that the names reflected the lands of the northern Mediterranean: the Lukka, Ekwesh, Tursha, Shekelesh, and Shardana were men from Lydia, Achaea, Tyrsenia (western Italy), Sicily, and Sardinia." De Rougé and others regarded Meryre's auxiliaries-these "peoples de la mer Méditerranée"- as mercenary bands, since the Sardinians, at least, were known to have served as mercenaries already in the early years of Ramesses the Great. Thus the only "migration" that the Karnak Inscription seemed to suggest was an attempted encroachment by Libyans upon neighboring territory."

^ Jump up to: a b c d e Drews 1995, p. 49.

- Gale, N.H. 2011. ‘Source of the Lead Metal used to make a Repair Clamp on a Nuragic Vase recently excavated at Pyla-Kokkinokremos on Cyprus'. In V. Karageorghis and O. Kouka (eds.), On Cooking Pots, Drinking Cups, Loomweights and Ethnicity in Bronze Age Cyprus and Neighbouring Regions, Nicosia.

- O'Connor & Cline 2003, p. 112-113.

Marejeo mengine[hariri | hariri chanzo]

- Hasel, Michael G. 1994. “Israel in the Merneptah Stela," Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 296, pp. 45–61.

- Hasel, Michael G. 1998. Domination and Resistance: Egyptian Military Activity in the Southern Levant, 1300–1185 BC. Probleme der Ägyptologie 11. Leiden: Brill Publishers. ISBN 90-04-10984-6

- Hasel, Michael G. 2003. "Merenptah's Inscription and Reliefs and the Origin of Israel" in Beth Alpert Nakhai (ed.), The Near East in the Southwest: Essays in Honor of William G. Dever, pp. 19–44. Annual of the American Schools of Oriental Research 58. Boston: American Schools of Oriental Research. ISBN 0-89757-065-0

- Hasel, Michael G. 2004. "The Structure of the Final Hymnic-Poetic Unit on the Merenptah Stela." Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 116:75–81.

- James, T. G. H. 2000. Ramesses II. New York: Friedman/Fairfax Publishers. A large-format volume by the former Keeper of Egyptian Antiquities at the British Museum, filled with colour illustrations of buildings, art, etc. related to Ramesses II

Viungo vya nje[hariri | hariri chanzo]

- Egypt's Golden Empire: Ramesses II

- Ramesses II

- Usermaatresetepenre

- Ramesses II Usermaatre-setepenre (about 1279–1213 BC)

- Egyptian monuments: Temple of Ramesses II

- List of Ramesses II's family members and state officials Archived 24 Julai 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- Newly discovered temple Archived 24 Septemba 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- Full titulary of Ramesses II including variants

| Makala hii kuhusu mtu wa Biblia bado ni mbegu. Je, unajua kitu kuhusu Ramses II kama habari za maisha au kazi yake? Labda unaona habari katika Wikipedia ya Kiingereza au lugha nyingine zinazofaa kutafsiriwa? Basi unaweza kuisaidia Wikipedia kwa kuihariri na kuongeza habari. |